MULTY-CHANNEL VIDEO INSTALLATION, 2008

15-CHANNEL VIDEO INSTALLATION WITH 2-CHANNEL SOUND

with Elli Brumen, Ingunn St. Svavarsdottir, Lucian Peterca, Oleg Mavromatti, Melisa Maida, Zaneta Schmiedale, Alexander Kwale, Gabriele Heller, Rene Beekman, Vulcho Kamarashev, Alessandro Vincentelli, Violeta Januskievica Cecilia Stenbom, Zuzana Hruskova, Gareth Harding

Can European identity be defined? What parameters and elements dictate our understandings of ‘European identity’?

The specific questions on which the work is based are about the subject: ‘at home’. What does it mean to ‘feel at home’? What or where could be ‘at home’? Does a geographical location or national belonging today define ‘at home’? Is it possible that identity is affected by nationality in times of global transforma- tion and migration processes? These issues, seen from the perspective of the migrant, are central to this work.

15 stories and 15 languages have been re-distributed so that each one is performed by different person and in a different language than the accordant ‘original’.

SUPPORTED BY BMUKK / AUSTRIA, ISIS ARTS / UK

_

Nothing will be the same as it was,

Even enjoying the same things

won’t be the same. Our sorrows

will differ one from the other and we

will differ one from the other in our worries.

(From Piotr Sommer’s poem, ‘Continued’, in Piotr, Sommer, Continued, Tarset: Bloodaxe, 2005)What does it mean to leave one’s homeland? To discover that you are not who you once thought you were? Is it the journey that has somehow changed you? Or is it everything else? Every ordinary experience that you have, or that you have had, or that you thought you had, all these are now altered. Everything is odd. Bread. Rain. The child on the bus talking to her mother. You’re never going back. Because even if you did go back, the very thing that you were going back to – the everything that once you loved or hated or were indifferent to, would all be different now. That is to say, it would all be gone. This is why we need stories – because stories give continuity to our discontinuity. They describe – in a way that ‘objective’ or statistical descriptions never can – the ongoing complexity of lived experience. The collected stories in Ventzislavova’s work, function thus – focusing us in on the very density of ‘the migrant’s’ experience; revealing the way that ‘migration’ doesn’t just stop on ‘arrival’, but persists and continues long after the physical act of movement is over. A Bulgarian artist, now living in Vienna, Borjana Ventzislavova is herself no stranger to the experience of being a stranger. Perhaps this is why We Shall Overswim, 2008 (and much of her previous work) is made out of stories. More specifically, perhaps this is why Ventzislavova’s work is made out of counter-narratives.

The term ‘counter-narratives’ was influentially used by Homi K Bhabha in his essay ‘DissemiNation: Time, Narrative and the Margins of the Modern Nation’ (1990: 291-320). It refers to those narratives, histories and stories which, when woven together, disrupt the ‘essentialist’ identity of the nation-state. In Bhabha’s analysis, these stories are more accurately called ‘counter-narratives’ because of the way they trouble us – they at once evoke and at the same time erase the boundaries of the home/land/ nation which we once dreamt were ‘ours’. That ‘imagined’ continuity of culture and custom that we used to call ‘our country’, is now unsettled by other narratives – by the stories of those who have made their homes amongst ‘us’. ‘Counter-narratives’ are a bit like unexploded bombs. They may never be fatal, but can they still frighten us, because they remind us of the instability and the fragility of ‘everyday life’ as we have constructed it. Counter-narratives make us realize moreover, that this instability is not a passing malaise, but a permanent facet of contemporary life.

Another way of saying this is that Ventzislavova’s work is about the politics of human displacement in a changing European world. Such a statement however obscures – conceals even – the real complexity of the lives that populate contemporary Europe. It gives us no faces. It doesn’t show us the persecution or the poverty or the armed conflict (both within and beyond Europe) from which many people are fleeing. Neither does it give us any of the other sides of the story – the bits about hope and about socializing and about struggling to belong. Ventzislavova’s characters, in contrast with terminology and statistics, tell us about all of these things. They hint at the incommensurable experiences of struggle and survival that lie behind words like ‘migration’. They tell us about those who sleep well and about those who will never sleep well again. They tell us about those who dream of front gardens and those who dream of forests. And they speak, in a way that abstract language cannot, about what it means to have a ‘home’ and to leave it – voluntarily or involuntarily. Finally, they show us the inadequacy of words like ‘migration’ and ‘home’ – words which fail to say anything about the complexity of ‘European’ lives today. What is ‘home’ anyway? Is it a place where all tensions are resolved and soothed away or is it a place that is haunted by the awful, the unspoken, the unmentionable? Nikos Papastergiadis tells us that modern use of the word ‘homeland’ is “predicated on the existence of a nation-state” (2000:54). It is presumed, Papastergiadis argues, that “since everyone is a member of a national community, they are also ‘at home’ in that nation-state”. However, as Papastergiadis then goes on to show, such a construction overlooks the vast number of people who have become homeless, who have left or taken flight from their ‘own’ nation – or who, for historical reasons, do not have a homeland/state at all (e.g. the Palestinians, the Kurds, Romanies and many others). The ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees’ who populate Ventzislavova’s work are complex constructions. They do not tell their ‘own’ stories, but instead they give us (in any one of a number of European languages) the story of some other ‘migrant’. All the complex and irreducible experiences of their lives are thus churned up together. They are – literally and metaphorically – translated. And yet they continue to exist somewhere in the (untranslatable) process of toing and froing between one place and another, or between one voice and another.

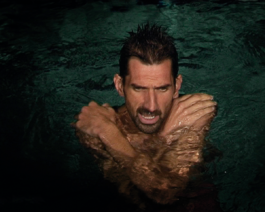

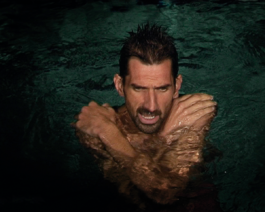

Questions of identity are always posed in relation to space. The dynamics of our movement in space, our ability to move, says more about who we are, than words like ‘Bulgarian’, ‘Norwegian’, ‘Latvian’, or even, ‘European’. The participants/protagonists in Ventzislavova’s work have to keep moving to stay afloat. Quite literally, they have to do something to keep their heads above water. Lit only by a spotlight, they bob up and down in a weirdly abstract space, surrounded by dark watery sounds. You could say that because of this setting, because of this condition, they are forced into perpetual movement. Alternatively, you could say that they have been activated by the very water that they tread. Questions of identity are interwoven in time as well as in space. Ventzislavova’s protagonists have several parallel lives/roles to play. They are migrants and storytellers and actors and characters in their own and in someone else’s story. Their identities, their lives are not knowable. Or at least, they are only knowable in the passage between telling/told/being/becoming. Their lives float between ‘here’ and ‘somewhere else’ – between ‘now’ and ‘then’ and ‘what might be’. Identity – European or otherwise – is what emerges from this process. It’s the remainder between becoming and disappearing. Ultimately, what Ventzislavova’s work evokes is not identity per se, but the interconnectedness of different identities – the crossover between different narrative times and spaces – perhaps what Homi K Bhabha called the “insurmountable agonism of the living” (1990:302).

Bernadette Buckley

References: Homi K Bhabha, ‘Dissemination: Time Narrative and the margins of the Modern Nation’ in Nation and Narration, London: Routledge, 1990 Nikos Papastergiadis, The Turbulence of Migration: Globalisation, Deterritorialisation and Hybridity, Malden MA: Polity, 2000 Piotr Sommer, Continued, Tarset: Bloodaxe, 2005 Bernadette Buckley is Convenor of the MA in Art & Politics at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research interests cut across several fields from art to politics, philosophy and cultural studies. She has published on themes related to art, war, terror/ism and more broadly, on the relationship between art and politics. Recent publications include ‘Mohammed is Absent. I am Performing’: Contemporary Iraqi Art and the Destruction of Heritage’ in The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq, eds., Stone & Farchakh Bajjaly, Boydell, 2010 (winner of the AIA James R. Wiseman book award; ‘Forum: Art and Politics’, in Postcolonial Studies, 2010; ‘The Workshop of Filthy Creation: Or Do Not Be Alarmed, This is Only a Test’ in RIS, 2009; ‘Terrible Beauties’ in B.rumaria: Art Aesthetics Politics, 2009. She has worked on a number of funded research projects for AHRC, ACE, En-quire, Heritage Lottery and the Wellcome Foundation.

MULTY-CHANNEL VIDEO INSTALLATION, 2008

15-CHANNEL VIDEO INSTALLATION WITH 2-CHANNEL SOUND

with Elli Brumen, Ingunn St. Svavarsdottir, Lucian Peterca, Oleg Mavromatti, Melisa Maida, Zaneta Schmiedale, Alexander Kwale, Gabriele Heller, Rene Beekman, Vulcho Kamarashev, Alessandro Vincentelli, Violeta Januskievica Cecilia Stenbom, Zuzana Hruskova, Gareth Harding

Can European identity be defined? What parameters and elements dictate our understandings of ‘European identity’?

The specific questions on which the work is based are about the subject: ‘at home’. What does it mean to ‘feel at home’? What or where could be ‘at home’? Does a geographical location or national belonging today define ‘at home’? Is it possible that identity is affected by nationality in times of global transforma- tion and migration processes? These issues, seen from the perspective of the migrant, are central to this work.

15 stories and 15 languages have been re-distributed so that each one is performed by different person and in a different language than the accordant ‘original’.

SUPPORTED BY BMUKK / AUSTRIA, ISIS ARTS / UK

_

Nothing will be the same as it was,

Even enjoying the same things

won’t be the same. Our sorrows

will differ one from the other and we

will differ one from the other in our worries.

(From Piotr Sommer’s poem, ‘Continued’, in Piotr, Sommer, Continued, Tarset: Bloodaxe, 2005)What does it mean to leave one’s homeland? To discover that you are not who you once thought you were? Is it the journey that has somehow changed you? Or is it everything else? Every ordinary experience that you have, or that you have had, or that you thought you had, all these are now altered. Everything is odd. Bread. Rain. The child on the bus talking to her mother. You’re never going back. Because even if you did go back, the very thing that you were going back to – the everything that once you loved or hated or were indifferent to, would all be different now. That is to say, it would all be gone. This is why we need stories – because stories give continuity to our discontinuity. They describe – in a way that ‘objective’ or statistical descriptions never can – the ongoing complexity of lived experience. The collected stories in Ventzislavova’s work, function thus – focusing us in on the very density of ‘the migrant’s’ experience; revealing the way that ‘migration’ doesn’t just stop on ‘arrival’, but persists and continues long after the physical act of movement is over. A Bulgarian artist, now living in Vienna, Borjana Ventzislavova is herself no stranger to the experience of being a stranger. Perhaps this is why We Shall Overswim, 2008 (and much of her previous work) is made out of stories. More specifically, perhaps this is why Ventzislavova’s work is made out of counter-narratives.

The term ‘counter-narratives’ was influentially used by Homi K Bhabha in his essay ‘DissemiNation: Time, Narrative and the Margins of the Modern Nation’ (1990: 291-320). It refers to those narratives, histories and stories which, when woven together, disrupt the ‘essentialist’ identity of the nation-state. In Bhabha’s analysis, these stories are more accurately called ‘counter-narratives’ because of the way they trouble us – they at once evoke and at the same time erase the boundaries of the home/land/ nation which we once dreamt were ‘ours’. That ‘imagined’ continuity of culture and custom that we used to call ‘our country’, is now unsettled by other narratives – by the stories of those who have made their homes amongst ‘us’. ‘Counter-narratives’ are a bit like unexploded bombs. They may never be fatal, but can they still frighten us, because they remind us of the instability and the fragility of ‘everyday life’ as we have constructed it. Counter-narratives make us realize moreover, that this instability is not a passing malaise, but a permanent facet of contemporary life.

Another way of saying this is that Ventzislavova’s work is about the politics of human displacement in a changing European world. Such a statement however obscures – conceals even – the real complexity of the lives that populate contemporary Europe. It gives us no faces. It doesn’t show us the persecution or the poverty or the armed conflict (both within and beyond Europe) from which many people are fleeing. Neither does it give us any of the other sides of the story – the bits about hope and about socializing and about struggling to belong. Ventzislavova’s characters, in contrast with terminology and statistics, tell us about all of these things. They hint at the incommensurable experiences of struggle and survival that lie behind words like ‘migration’. They tell us about those who sleep well and about those who will never sleep well again. They tell us about those who dream of front gardens and those who dream of forests. And they speak, in a way that abstract language cannot, about what it means to have a ‘home’ and to leave it – voluntarily or involuntarily. Finally, they show us the inadequacy of words like ‘migration’ and ‘home’ – words which fail to say anything about the complexity of ‘European’ lives today. What is ‘home’ anyway? Is it a place where all tensions are resolved and soothed away or is it a place that is haunted by the awful, the unspoken, the unmentionable? Nikos Papastergiadis tells us that modern use of the word ‘homeland’ is “predicated on the existence of a nation-state” (2000:54). It is presumed, Papastergiadis argues, that “since everyone is a member of a national community, they are also ‘at home’ in that nation-state”. However, as Papastergiadis then goes on to show, such a construction overlooks the vast number of people who have become homeless, who have left or taken flight from their ‘own’ nation – or who, for historical reasons, do not have a homeland/state at all (e.g. the Palestinians, the Kurds, Romanies and many others). The ‘migrants’ and ‘refugees’ who populate Ventzislavova’s work are complex constructions. They do not tell their ‘own’ stories, but instead they give us (in any one of a number of European languages) the story of some other ‘migrant’. All the complex and irreducible experiences of their lives are thus churned up together. They are – literally and metaphorically – translated. And yet they continue to exist somewhere in the (untranslatable) process of toing and froing between one place and another, or between one voice and another.

Questions of identity are always posed in relation to space. The dynamics of our movement in space, our ability to move, says more about who we are, than words like ‘Bulgarian’, ‘Norwegian’, ‘Latvian’, or even, ‘European’. The participants/protagonists in Ventzislavova’s work have to keep moving to stay afloat. Quite literally, they have to do something to keep their heads above water. Lit only by a spotlight, they bob up and down in a weirdly abstract space, surrounded by dark watery sounds. You could say that because of this setting, because of this condition, they are forced into perpetual movement. Alternatively, you could say that they have been activated by the very water that they tread. Questions of identity are interwoven in time as well as in space. Ventzislavova’s protagonists have several parallel lives/roles to play. They are migrants and storytellers and actors and characters in their own and in someone else’s story. Their identities, their lives are not knowable. Or at least, they are only knowable in the passage between telling/told/being/becoming. Their lives float between ‘here’ and ‘somewhere else’ – between ‘now’ and ‘then’ and ‘what might be’. Identity – European or otherwise – is what emerges from this process. It’s the remainder between becoming and disappearing. Ultimately, what Ventzislavova’s work evokes is not identity per se, but the interconnectedness of different identities – the crossover between different narrative times and spaces – perhaps what Homi K Bhabha called the “insurmountable agonism of the living” (1990:302).

Bernadette Buckley

References: Homi K Bhabha, ‘Dissemination: Time Narrative and the margins of the Modern Nation’ in Nation and Narration, London: Routledge, 1990 Nikos Papastergiadis, The Turbulence of Migration: Globalisation, Deterritorialisation and Hybridity, Malden MA: Polity, 2000 Piotr Sommer, Continued, Tarset: Bloodaxe, 2005 Bernadette Buckley is Convenor of the MA in Art & Politics at Goldsmiths, University of London. Her research interests cut across several fields from art to politics, philosophy and cultural studies. She has published on themes related to art, war, terror/ism and more broadly, on the relationship between art and politics. Recent publications include ‘Mohammed is Absent. I am Performing’: Contemporary Iraqi Art and the Destruction of Heritage’ in The Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq, eds., Stone & Farchakh Bajjaly, Boydell, 2010 (winner of the AIA James R. Wiseman book award; ‘Forum: Art and Politics’, in Postcolonial Studies, 2010; ‘The Workshop of Filthy Creation: Or Do Not Be Alarmed, This is Only a Test’ in RIS, 2009; ‘Terrible Beauties’ in B.rumaria: Art Aesthetics Politics, 2009. She has worked on a number of funded research projects for AHRC, ACE, En-quire, Heritage Lottery and the Wellcome Foundation.